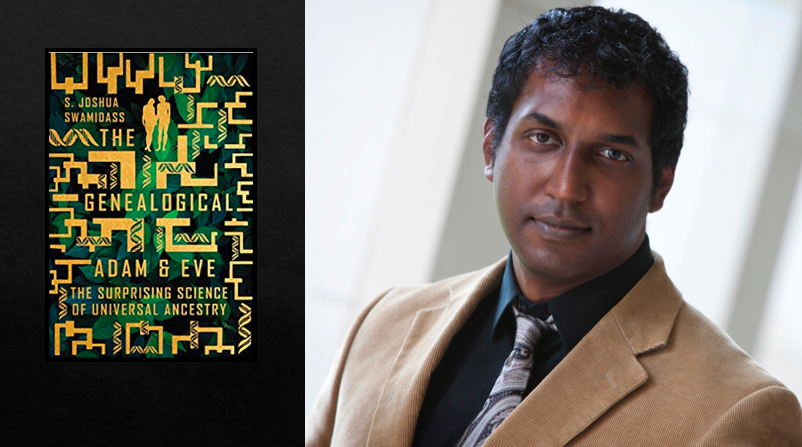

Dr. Josh Swamidass has written a provocative new book titled The Genealogical Adam and Eve, which releases next month. Essentially, the question he asks is, “Are evolution and a historical Adam compatible?” And his surprising answer is “Yes.” While Josh and I differ on the status of evolution, I found his book thoughtful, provocative, and written in a gracious spirit towards those who see the world differently.

This is the second part in our series reflecting on the 160th anniversary of the release of The Origin of Species. Earlier this week, I released a blog by my colleague Douglas Axe on the current status of evolutionary theory. Along with that post, this new book by Swamidass is one worth wrestling with. Even if you are not convinced, Swamidass will give you a ton to think about theologically and scientifically. But start by checking out this brief interview related to his spiritual journey, current research, and approach to Genesis:

SEAN MCDOWELL: Can you briefly share about your journey into questions related to science and faith?

JOSHUA SWAMIDASS: I am a scientist in the Church and a Christian in science. My journey through science is a search for a confident faith.

Raised in a Young Earth Creationist household. My mother talked to toddler me about Jesus, and I believed. As a middle schooler, I read More than a Carpenter, and came to clearly see the Resurrection. At the empty tomb, my faith became my own.

As a student, I was drawn to science, but science grew my doubts. Searching for confidence, I turned to anti-evolution arguments of various sorts. At the time, these arguments were comforting, but they drew me away from Jesus. I became like Peter in the garden when the soldiers came (Matthew 26:47-56). Jesus seemed like a powerless bystander, in need of my defense, irrelevant to the debate, but threatened all the same.

Scripture testifies of a different Jesus. In losing sight of the One who needs no defense, I struggled for many years with an insecure and threatened faith. Something had to change, and it did. In time and through grace, I remembered the same Gospel my mother first shared with me. The same gospel that Paul confesses (I Corinthian 15:3-7), and the “one sign” that Jesus gives to skeptics: his death and Resurrection (Matthew 12:38-42). I found a different apologetic, offering “explanation” (I Peter 3:15), rather than a “defense,” of the hope growing within me.

I am a scientist now. Science is powerful and grand, full of the beauty and mystery of God’s creation. I have searched all over. Jesus, still, is greater than all I found in science. Whether evolution is true or not, God raised this man Jesus from the dead. This is how I know that God is exists, that He is good, and that He wants to be known.

Here, at the empty tomb again, I found a confident faith. I left my anti-evolution idols. I followed Him.

MCDOWELL: What do you see as the proper relationship between theology and science?

SWAMIDASS: I understand science as a conversation among scientists. Theology is a conversation among theologians, but it is also a conversation in the Church.

The proper relationship between theology and science is dialogue, a meaningful exchange between two communities with different ways of understanding the world. Each community, theological and scientific, has its own legitimacy and autonomy. Good conversations are shaped by constructive resistance, not capitulation. Dialogue includes an exchange of good-faith questions. Whether they come from theology or science, questions should be taken seriously, answered with honesty, rigor, and empathy.

What should the Church expect to gain from dialogue? A coherent theological voice could rise, making sense of everything together. Even in a scientific world, we could understand, and we could be understood.

C.S. Lewis gets it right in Is Theology Poetry? Science describes the world as we find it, but in a particular, limited way. Even when correct, the scientific understanding of the world is incomplete. The task of theology, then, is to complete the story, making sense of everything together.

Confident theology engages science, recognizing the legitimacy of scientific findings, but also extending beyond. Lewis paints a beautiful picture. Science is a dream, but theology is the waking world. The waking world contains the dreaming world. In the same way, theology is not science, but it is meant to contain science and its findings. Theology is to be, in this way, the story that contains the other stories.

The grand story, the true story that makes sense of the world, this theology is forged in dialogue. A confident and understandable voice is possible, centered on Jesus, not Adam. This theological voice is what the Church stands to gain in dialogue with science.

MCDOWELL: There’s has been a lot of talk about the historical Adam lately. What does your new book The Genealogical Adam & Eve contribute to this discussion?

SWAMIDASS: The renown philosopher of biology, Alan Love, observes, “This is one of those rare books that changes the conversation.”

This week is the 160th anniversary of Origin of the Species, the book by Darwin that first proposed evolution. Quickly, the conflict between evolution and the traditional account of Adam and Eve seemed certain. Most readers of Genesis the last few thousand years understood Adam and Eve as ancestors of us all, de novo created without parents, less than 10,000 years ago in the Middle East. Both creationists and evolutions agreed we must choose between this traditional account and evolutionary science. In response, some Christians argued that non-traditional understandings of Adam and Eve could be a faithful response to evolution.

Everyone agreed, in the end, that evolutionary science was in conflict with the traditional de novo account of Adam and Eve. In recent decades, population genetics seems to establish this conflict as an undeniable fact.

I am a skeptic of this conflict. The more I learned of evolutionary science, the more skeptical I grew.

My book explains why there is far less conflict than we imagined. Entirely consistent with the genetic evidence, Adam and Eve, ancestors of us all, could been de novo created less than 10,000 years ago in the Middle East. The only way that evolutionary science presses on this story is by suggesting, alongside Scripture and the Genesis tradition, that there were people outside the garden with whom their lineage interbred.

Even if this traditional understanding of Adam and Eve is false, we do not know it false from evolutionary science. Certainly, some versions of the traditional account of Adam and Eve are in conflict with the evidence. Some versions, however, are not in conflict.

This finding, to be clear, is articulated from within mainstream science, relying on science that is well-established, but overlooked. The great Alan Templeton, author of a well-known textbook on population genetics, endorses this book. Nathan Lents, an atheist biologist, endorsed my book, also, explaining why in a widely read Op-Ed in USA Today.

As biologist Darrel Falk confessed in his endorsement, “I am one of the many scientists who have maintained that the existence of Adam and Eve as ancestors of all people on earth is incompatible with the scientific data;” we “were wrong.”

MCDOWELL: You make the surprising claim that there is no incompatibility between evolution and traditional readings of Genesis. How do you reconcile the two? And what does it mean for old and young earth creationists?

SWAMIDASS: Some of us are convinced that evolution is a myth. Some of us are convinced that Adam and Eve are a myth. Either way, we can travel together into a though experiment, perhaps finding common ground. What if both stories can be true at the same time?

Conflict arose because we misunderstood three concepts: ancestor, human, and mystery. On ancestor, scientific findings are often articulated in the language of genetics, but Scripture is concerned with genealogical ancestry, not genetic ancestry. On human, theologians can legitimately define the term in a different way than scientists. On mystery, we missed that neither science nor Scripture tells us the whole story. The Genesis tradition, in particular, includes mystery outside the Garden.

With these three misunderstands cleared up, there is far less conflict than we once believed.

How does this affect old- and young-earth creationism? For the first time, there is a theological story that contains both evolutionary science alongside the traditional de novo account of Adam and Eve in the same physical world. Our certainty of conflict was wrong. We misunderstood the findings of mainstream science.

The Genealogical Adam and Eve reshuffles the deck. As the old-earth creationist Ken Keathley puts it, this “changes the game.”

MCDOWELL: What are your hopes for this new book?

SWAMIDASS: The Church is divided on evolution. Origins is a quagmire, an ugly argument. I hope this book starts a new conversation where we can find a better way together.

Much less is at stake than we once feared. Whether or not evolution is true, some traditional de novo accounts of Adam and Eve are entirely consistent with the evidence. Creationism, at its best, is about faithfulness to Scripture, not stubborn opposition to evolutionary science. If Scripture is the driving concern, there is far less reason to stake out an anti-evolution position.

Confident traditionalists might arise, unthreatened by evolution, whether it be true or false. In the book, I offer a speculative story of origins. This speculative story contains the story of evolutionary science and it contains the creationist understanding of Genesis I first learned as a child. A conversation is growing among theologians, exegetes, and thoughtful people in the Church. They are filling in and changing details, making sense of it all together. In this exchange, we are approaching the grand question together: what does it mean to be human?

Origins is a quagmire. There must be a better way. Whatever you personally believe, journey with me through this book. I see a better way, oriented around grand questions, centered on Jesus. Together, we might find a theological voice in our scientific world.

Let us find a peaceful science, that better way together.