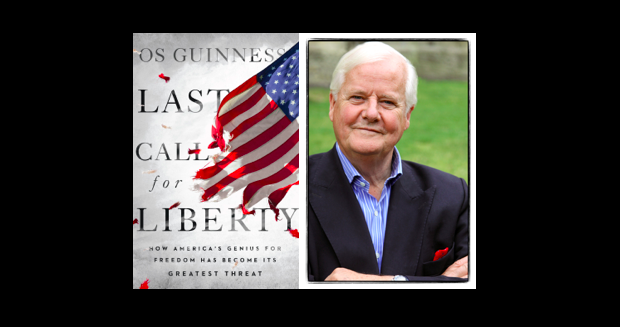

Book Review: Last Call for Liberty (Os Guinness)

SeanMcDowell.org

If America is the “land of the free,” why are there so many addictions and recovery groups? Why is there growing surveillance, deep financial indebtedness, and endless eruptions of rage from one group to another? Is American freedom at stake?

These are the kinds of questions Os Guinness explores in his most recent book Last Call for Liberty. His goal is not to answer each of these questions individually, but to address a larger crisis, which he considers as deep to America as the evil of slavery. Guinness believes it may even pose a greater threat to the American experiment than 20th century Soviet communism or Hitler’s National Socialism.

What is this grave threat? Guinness believes America is more divided–politically, economically, racially, ideologically, culturally, and religiously–than any time since the Civil War, which nearly ended its union. What accounts for this division? At the core, says Guinness, “The deepest division is rooted in the differences between two world-changing and opposing revolutions, the American Revolution of 1776 and the French Revolution of 1789, and their rival views of freedom and the nature of the American experiment” (p. 3). America is at a turning point deciding which revolution it will embrace.

Negative Freedom

According to Guinness, the theme of the French Revolution of 1789 was captured by Jean-Jacques Rosseau in his Social Contract: “Man is born free, but he is everywhere in chains.” In other words, freedom comes when mankind throws off any limits or shackles. Guinness refers to this as negative freedom, which is the ability to do whatever you want. If it feels good, do it.

Take the Marxist revolutions of the 20th century, for instance. They were based on the idea that mankind was shackled in economic chains and needed liberation from capitalist structures. Yet as Guinness notes, since these revolutions were utopian in nature and not grounded in reality, they end up bringing “progressive freedom through government control.” Similarly, says Guinness, multiculturalism, political correctness, and the sexual revolution were sold as movements of liberation, but have only brought bondage.

Positive Freedom

While freedom begins with the absence of coercion (negative freedom), there is also positive freedom, which is the power to do what you ought. This kind of freedom, says Guinness, “requires a vision of truth, character, ethics, and the common good–for unless we know the truth of who we are and how we are supposed to live and to live with others, we cannot hope to attain the freedom of being ourselves and offering the same freedom to others” (p. 87).

This is a radically different view of freedom. As G.K. Chesterton famously said, “You can free things from alien or accidental laws, but not from the laws of their own nature. You may, if you like, free a tiger from his bars; but do not free him from his stripes. Do not free a camel from the burden of his hump: You may be freeing him from being a camel.”

Positive freedom is not about doing as you please but doing as you ought. It involves aligning one’s life to reality; not trying to align reality to one’s whims. Positive freedom, at the root of the 1776 revolution, is about living in service for the good of all. This kind of freedom requires trust, character, promise-keeping, self-restraint, and alignment with reality.

The Exodus and Freedom

In one of the most interesting chapters, Guinness traces the American experiment in freedom back to the Exodus. He believes it is “the direct ancestor of the Fourth of July, and it holds the missing key to America’s independent, to America’s freedom, to America’s history, and therefore to the renewal of America’s freedom today.” It’s no coincidence, notes Guinness, that Nietzsche attacked the Exodus as the event that undermined the power-based view of freedom he advocated.

Why is this important? According to Guinness, the Exodus provides the model of a covenant-based government that relies upon trust, solidarity, character, and a commitment between parties to the principles of the union. And yet, he notes, “Martin Luther King Jr. hated racism and injustice no less passionately than today’s activists. But he believed in the American Revolution, so he appealed to the Declaration of Independence as America’s ‘promissory note.’”

Guinness fears people today are losing the commitment to the ideals of the 1776 Revolution and adopting ideas behind the 1787 Revolution. He believes freedom is at stake and the hour is now.

Concluding Thoughts

Last Call to Liberty is a thick and sobering book. It is thick in the sense of requiring considerable effort and time to unpack. It is not a light read. Guinness writes with remarkable elegance, but he wades into extensive philosophical and historical analysis that requires both focus and time. It was worth it to me. I read it twice.

It is also a sobering book. Guinness has been a social critic for a long time. When people as insightful, seasoned, and faithful as Os Guinness speak, I always listen. He does not write with alarmism, but with deep conviction-based concern about the state of freedom in America. If he is right, America is at a crossroads and may look radically different in a few short years.

For people who want to think deeply about culture today, I could not recommend this more book more highly. Guinness has the remarkable ability to see modern cultural events (e.g., kneeling at NFL games) through the lens of broad historical trends.

You may disagree with Guinness at points, as I do. But if you are a serious cultural thinker today, this is a must-read book.