SeanMcDowell.org

Dr. Craig Keener is one of the leading Biblical scholars today. He is the author of many vitally important books such as his 4-part commentary on Acts, his 2-part volume on miracles, and The Historical Jesus of the Gospels. His research contribution is simply gargantuan. And he is a genuinely nice guy with a remarkable story of conversion from atheism to Christianity.

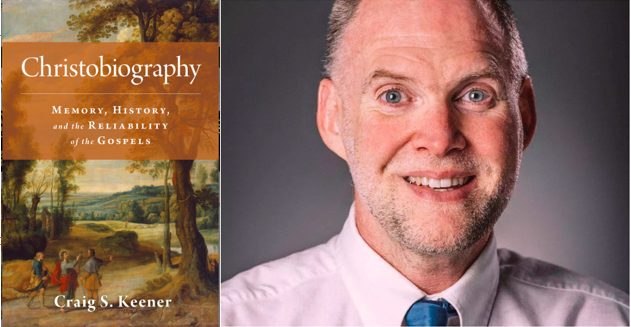

He has a new book releasing this month called Christobiography. As you can see below, he considers it one of his most important works. Dr. Keener was kind enough to answer a few of my questions. Check out the interview and please consider getting a copy of his latest book.

SEAN MCDOWELL: You have said that this is your most important academic book since the 4-part Acts commentary. What makes this book so important?

CRAIG KEENER: Scholars and non-readers of the Gospels often start with skeptical assumptions about the Gospels that no one would typically entertain for memoirs or biographies written today a comparable date after the events depicted. Of course, there are differences in the Gospels, but most of these are the sorts of differences that were common in ancient biographies. Ancient biographies were written differently from modern ones, but not in terms of making up events. The sort of flexibility we find there fits the kind of differences we find in the Gospels, but the historiographic character of the genre also leads us to expect that the Evangelists are recounting information that they believe happened. Given what we know of biographies of the period and methods of transmission, we should expect a reliable picture of Jesus in the Gospels.

MCDOWELL: The title is Christobiography. What is the significance of the title as it relates to the thesis of your book?

KEENER: The first ancient auditors, until they became familiar with the more specific genre of Gospels, would approach the Gospels as ancient biographies of Jesus. The question the book then addresses is, what should we expect (particularly historiographically) of such biographies? My originally proposed subtitle was, "Memories and Memoirs about Jesus." The publisher, I assume wanting to market well and sell more copies, relabeled the subtitle, "Memories, History, and the Reliability of the Gospels." This is also true, though in this book I don't get much into examining particular passages. My primary concern in this book is what our starting assumptions should be as we approach the Gospels.

How would we approach other biographies from the early empire written a comparable date after the events they describe? I look at some of these other biographies and show that we should normally trust the substance of the events they narrate. Why should anyone, Christian or non-Christian, approach the Gospels differently? To approach the Gospels with greater skepticism seems to me an expression of prejudice, unless one can adduce for such skepticism substantial reasons. I find wanting the reasons so far proposed.

MCDOWELL: What is one big apologetics takeaway from this new book?

KEENER: Obviously, Christians do not approach the Gospels as just any other book; we reverence them as God's word. Those who are positively hostile toward the Gospels usually likewise have religious/theological reasons for doing so (anti-religion can be as dogmatic as traditional religion). But to the extent that we can get people to use the same criteria we would use to study other biographies from the period (the point of the book), the Gospels provide quite a lot of information about Jesus. Readers from different perspectives are still going to approach the details from their different perspectives, so this approach does not resolve all the details. But details aside, we have in the Gospels so much historically likely information about Jesus, using basic methods that everyone should agree on, that this figure of Jesus in the Gospels should confront us and challenge us.

I don't go into all of that in this book, but if even half of the incidents and teaching in the Gospels is true, then the Gospels invite us to faith. Some of my more skeptical academic colleagues may demur from this conclusion, which is certainly their academic prerogative, but it seems to me a fully logical inference from the evidence. When I was an atheist, had this evidence been presented to me, I certainly would have had to grapple seriously with the figure of Jesus in the Gospels and his demands on me. Most people, however, have never been exposed to this evidence.

MCDOWELL: Generally speaking, how do you decide what projects to research and write?

KEENER: That varies from book to book and project to project. But I don't like to reinvent the wheel and just do what someone else has done adequately. If I write a commentary, I normally want it to contribute something new–not to supplant other commentaries, but not to simply compete with them either. Life is too short to waste on such competition. So where I see something that needs to be done, I try to do it or, now that I have PhD students, recommend such projects to them if they have interest. So many areas in NT scholarship have never been developed yet, while in some other areas dissertation-writers are piling on top of each other trying to write about currently fashionable ideas. The former requires more work in the primary sources and often interdisciplinary work; the latter sometimes ends up picking apart details in secondary scholarship and finding a minute niche to make a minimal contribution. Scholars have only recently been exploring more deeply the historiographic implications of ancient biography and its relationship to the Gospels (our mutual friend Mike Licona being one of those groundbreaking explorers).

MCDOWELL: Seriously, how do you possibly write so much meticulously-documented academic work?! What’s your “secret”?

KEENER: In terms of the documentation, it's important to take good notes on what you read and to file it in such ways that you can readily access it for whatever subject you might write about. I started this in days before we had computers, with index cards. It was much more tedious back then. (By the way, my decades-old index cards make me sneeze. So starting on computer is much preferred now! Though make sure to have good backups.) It's important to think of potential connections: e.g., how can the material that you're studying in other ancient sources shed light on biblical passages or themes.

In terms of getting a lot done, part of it is that I pursue it as part of my calling. I don't watch TV or sports, for example. That makes me a bore at table conversation, but does help me get my writing done. (My wife did convince me, after the Acts commentary, to do Facebook. So I'm not a total bore.)

In terms of surviving getting a lot done: The Lord keeps renewing my strength. I can't forget what he's done for me–how he converted me from atheism by a direct and utterly unmerited encounter with his Spirit in the gospel. Even when I was an atheist, I said that if I discovered that there really was a God, I would give him everything, because I would owe him everything. But the heart of my strength to keep working (and usually enjoying it) depends on my times of prayer and God renewing my strength. I really experience new grace from his Spirit each day.

You can get a copy of his new book here.